Despite the government’s decision to decentralize blood collection to health districts in 2013, it seems most people are still reluctant to donate their blood as Botswana is yet to reach the amount of blood units required for a population of two million people. While 40, 000 units of blood are needed annually, the country collects a maximum of 25, 000 units nationally.

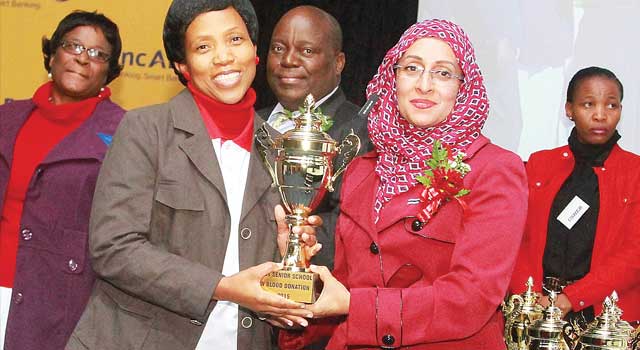

Permanent Secretary (PS) in the Ministry of Health, Shenaaz El-Halabi says there are many lives that were lost which could have been prevented easily had there been enough supply. The PS was speaking at the World Blood Donor Day over the weekend.

“The supply of adequate blood is a challenge all over the world and Botswana is not an exception. Our country has not been able to reach the 40, 000 units of blood required annually. The shortage of blood has in some unfortunate cases, resulted in loss of lives,” she said. She further said though the target is still far from being met, the decentralization of blood collection in 2013 had an immediate positive impact as 3, 552 units of blood were collected in 2014 at the new collection sites. It was for the first time they reached the 25, 000 units of blood since the creation of the National Blood Transfusion Centre in 2000.

She said they are planning to open four more blood collection clinics around the country with hopes of attracting more blood donors by bringing services to them. El Halabi explained that close to 60 per cent of units collected in Botswana come from students, exacerbating shortage during school holidays. “As we try to ensure adequate blood supply, we should not compromise on the safety of transfused blood. I would like to assure that my ministry is committed to provide necessary resources to ensure that blood given to patients is safe,” she said.

“The HIV prevalence in donated blood has decreased significantly from 7.7 per cent in 2003 to one per cent in 2014. The continued decline of HIV in donated blood is due to good recruitment strategies and proper selection of donors. These strategies are complemented by vigorous testing of donated blood and efficient quality management system,” El Halabi said.

For his part, a medical doctor at Princess Marina Hospital, Dr David Tamuhla said most of the blood they receive usually goes to abortion patients, followed by patients of chronic diseases such as cancer, kidney diseases, HIV, and surgery especially for road accidents and assaults. He urged more people to donate blood as it could save the lives of their loved ones. He challenged the Botswana Innovation Hub to sponsor local universities for research into alternatives of blood since it cannot be manufactured, as another option to saving lives without depending too much in donated blood.

With regards to abortion, he said; “Let’s talk to our young people, educate them and make them understand the consequences of their actions. Cases of abortion are currently using most of the blood we have because most of them are done illegally and dangerously, causing most to lose a lot of blood and risking their lives.”