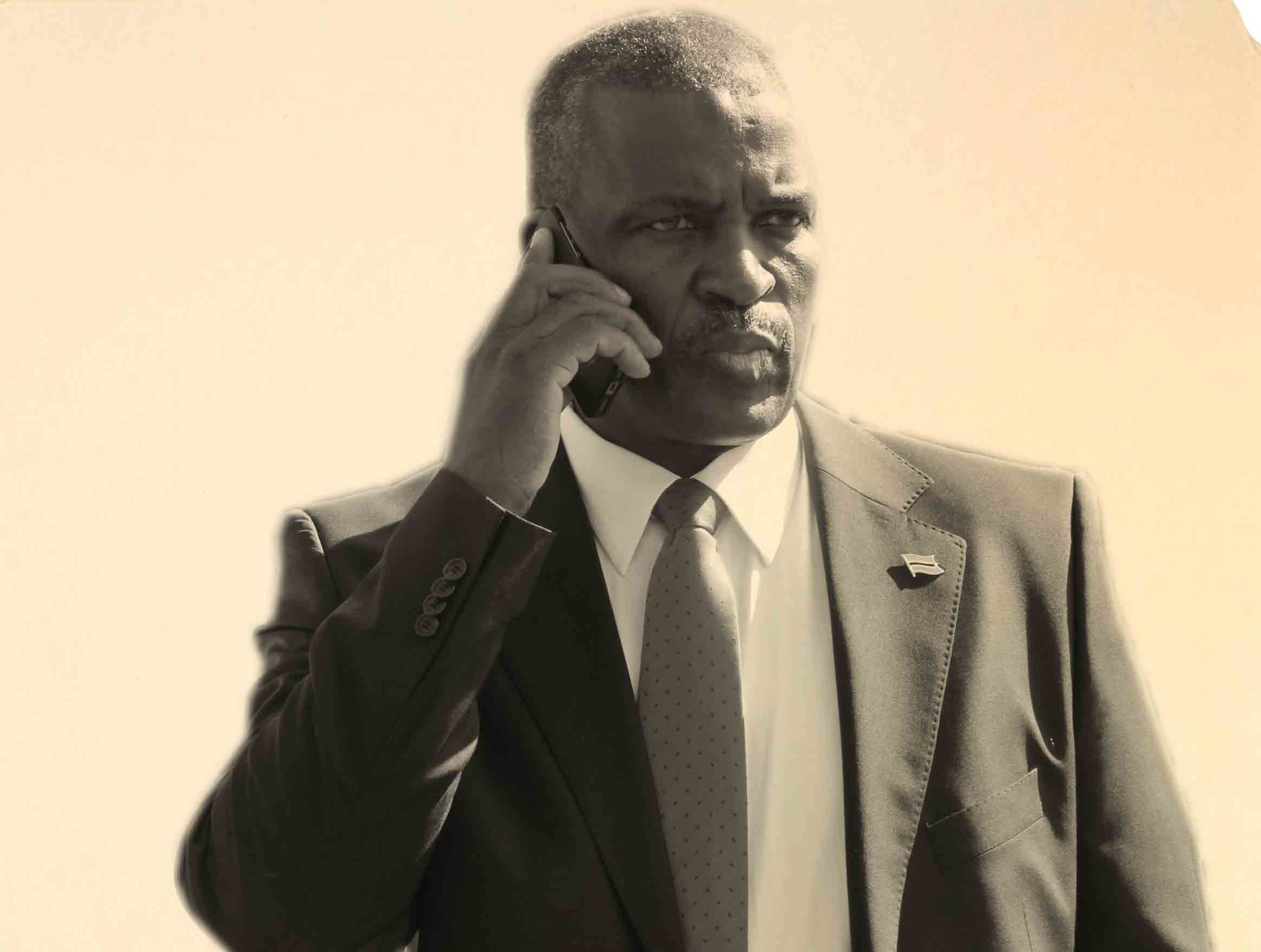

The state is reportedly in Malaysia in an effort to explore how they can penetrate through legal and privacy rights mounted by Kgosi through his health situation. Should they make a breakthrough, Kgosi will have to come back home to face the law. Staff Writer TEFO PHEAGE looks into the Malaysian extradition law which may take centre stage thereafter.

Extradition is the formal process by which someone accused or convicted of a crime has fled abroad is handed back to the jurisdiction of the country in which the crime was committed to face legal consequences of committing the crime.

Because the process of extradition involves the co-operation of two or more countries, some countries have concluded extradition treaties or arrangements with one another. Botswana, however, does not have such a treaty with Malaysia.

Treaties establish the conditions under which extradition to and from the signatory countries may take place and are legally binding on the signatory countries, obliging them to act in accordance with the agreed conditions. This aids greater transparency and clarity in the extradition process.

Section 6 of the Malaysian Extradition Act 1992 provides that for extradition to happen, a fugitive must have committed an extraditable offence. This is defined as an offence that is a crime in both countries and is punishable by at least one year of imprisonment or death. While Malaysia does not have an extradition treaty with Botswana, the country’s Minister of Home Affairs can allow a request from countries that Malaysia does not have such a treaty with.

Under Section 8, Malaysia’s extradition law imposes certain restrictions on who can be extradited and says the fugitive must not be wanted for a political crime but this does not include crimes motivated by politics, such as assassinations. Kgosi ‘s lawyers hold that their client is paying for the fallout between former president Ian Khama and President Mokgweetsi Masisi’s

The Malaysian law does not extradite people who are going to be punished for their race, religion, nationality or political opinion and emphasises that there must be no legal technicalities that could stop the extradition. The Malaysian extradition law states that the procedure for an extradition entails a requesting country sending a warrant for the arrest of a fugitive to the Minister of Home Affairs who verifies the document before telling a magistrates court to issue the warrant sought.

The magistrate can also issue the warrant based on information from INTERPOL (the International Criminal Police Organisation).When the fugitive is caught, they are put before a Sessions Court in Malaysia and given a chance to show evidence that they should not be extradited. If the Sessions Court accepts the evidence, the fugitive will be released. But if a preliminary case is proven, the fugitive is locked up until the minister orders their surrender to the requesting country. The law also empowers the fugitive to challenge his detention as unlawful, a process development that may prolong the entire process.

In Kgosi’s case, legal experts say an issue that may arise along the way is the right to his health information and privacy, as well as the right of law enforcement agencies to access the information without Kgosi’s consent. There are two types of situations where a health service may use or share a patient’s health information without a patient’s consent.

One is when someone else’s health or safety is seriously threatened and the information would help. This arises in situations of someone being unconscious and paramedics, doctors and nurses need to know if the person is allergic to any drugs. Another situation is when the information would reduce or prevent a serious threat to public health or safety. An example of this may be if a person’s health information could prevent or reduce a serious contagious illness and the public needs to be warned.

However, medical literature suggests that there are certain exemptions that may apply in law enforcement situations and in courts of law. Kgosi’s Malaysian doctor, Dr. Sivalingam Raja Gopal, says Kgosi is seriously ill and needs attention. Even so, Dr. Gopal has been known to defeat the ends of justice.