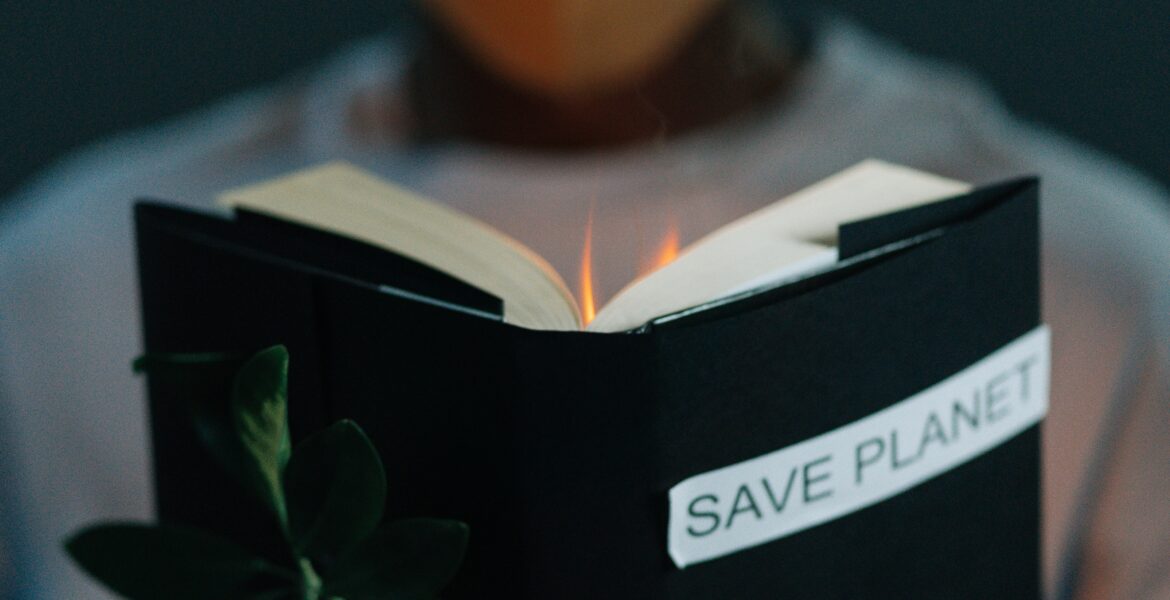

TSHEPHO MOYO talks to a few climate activists and finds ongoing projects that point

to profound commitment to rehabilitating the planet

As the United Nations Climate Summit COP27 goes into its second week, the expectations for climate solutions addressing the unequal impact of climate change in the world rise.

The reality is that African nations (and many other developing countries) are experiencing most destructive effects of climate change, yet the continent produces less than 4% of greenhouse gas emissions. A reflection of this minimal contribution is the fact that at least 75% of the global population without access to electricity lives in sub-Saharan Africa.

This crippling energy deficit curtails manufacturing and economic development. We spoke to four young people with a keen interest in climate solutions in Botswana about their expectations from COP27.

Kabo Nginya is a communications strategist, a climate change activist, and an active member of Resilient Frontier that advocates for loss and damage and adaptation practices at community level.

He has been engaging with communities to seek ways in which they can strategically adapt to climate change issues affecting us, and looking to invest in “climate enterprise” to attain sustainable development goals through a resilient community that can fend for themselves with resources they have in sustainable and effective ways.

Asked what changes he would like to see in Botswana’s policies after COP27, Nginya says Botswana’s current policy on climate change is the best we have so far as it is aligned with most climate change issues and mitigation. However, he believes there is space for review on issues around climate-related loss and damage compensations.

Granny Lesiemang is the founder and managing director of Clauseph Enterprises, a business started with the vision of rural industrialisation and economic empowerment through impactful projects that can grow communities.

Asked how her business attempts to provide climate solutions, she said their current project is the Clean Cooking initiative which is focused on manufacturing energy efficient biomass stoves and clean, solid biomass fuels by recycling agricultural waste and addressing bush encroachment in Botswana’s grazing lands.

Lesiemang noted that while COP27 is encouraging the world to move away from fossil fuels due to their impact on the environment, the reality of African rural communities is that clean energy solutions will still need to fit the lifestyles. A lot of the suggested clean energy solutions are costly to start and resources are limited in developing countries.

This is why Clauseph Enterprises believes in starting with what they already have access to – their biomass fuels are focused on using waste or invasive plant species that negatively impact climate rather than cutting down trees and contributing to deforestation. She believes that a missing link in the climate change conversations is businesses like hers that are implementing solutions to climate change through community mobilisation and engagement focused on adding value to the communities they are based in.

Sade, who is also known by their artist name Rrangwane, is a spiritually inclined artist and cultural worker who uses trans-disciplinary approaches to navigate the spectrum of decolonising and indigenising the personal and political self. As a marginalised member of society, Rrangwane centres on climate adaptability and resilience in their work.

In 2021, they launched an art project titled “Semausu Sa Pula Ya Kgojane,” which focused on the intersections between sustainable art, climate change and indigenous knowledge. The art installation discussed knowledge around African rituals of rainmaking and the role that indigenous knowledge may have in conversations about conservation and climate adaptability in a post-colonial world.

Sade believes that climate justice is crucial to the everyday lives of Batswana and other Africans, particularly considering that the global north is responsible for the majority of the climate change we are experiencing today. However, they are concerned that rural communities are being left out of conversations about climate change in Botswana despite the fact that their lives are the most disrupted by the drastic changes.

Lorraine Kinnear is a storyteller and communications professional in the climate action space. She has been taking part at COP in the Global Landscapes Forum as well as the Climate Action Innovation Zone, both organisations playing a huge role in policy development around the green use of natural resources that also protect the land rights of local dwellers of a specific question.

She believes that there is a lot that still needs to be done and that people can make such a huge impact in planetary restoration if they embrace their own African home-grown solutions. In terms of Botswana’s own journey with climate resilience, Kinnear believes that there are already policies in place that are not being put effectively to use. She highlights the need for Botswana to encourage uptake of programmes such as the National Environmental Fund (NEF) and allow the first few participants to fail fast so growth can be quick as we learn from the mistakes of each cohort.

“Another aspect that I believe is a low hanging fruit for us is to implement climate education into our basic education curriculum,” she says. “That’s how we can hasten interest in such spaces.

“Most people feel slightly misaligned from this cause because of lack of basic understanding and I believe if we drive that education aspect from the grassroots, we are more likely to catch the impressionable minds of the youth who will be mostly affected by climate change over the next few years, anyway.”