It is with some trepidation that I write this article simply because of the magnitude of the personalities involved in my subject matter…but anyway, here it goes. This follows the correction made by Rre Festus Mogae in a letter he wrote to Mmegi in which he expressed owing an apology to Rre David Magang for the “misapprehension” of his views during an interview over how Water Utilities treated the Phakalane Estates magnate.

Initially, it came out as if he considered Rre Magang’s actions “criminal” for building a private township and then “getting [the necessary] utilities free”. In the correction, it was Water Utilities that he considered “criminal” for insisting that Phakalane Estates pay for the pipeline from Gaborone to the Estate as well as the necessary water tower – which infrastructure, quite evidently, they benefit from when billing water usage by Phakalane residents and, perhaps, other settlements along the way, north of Gaborone, that benefit from that established infrastructure.

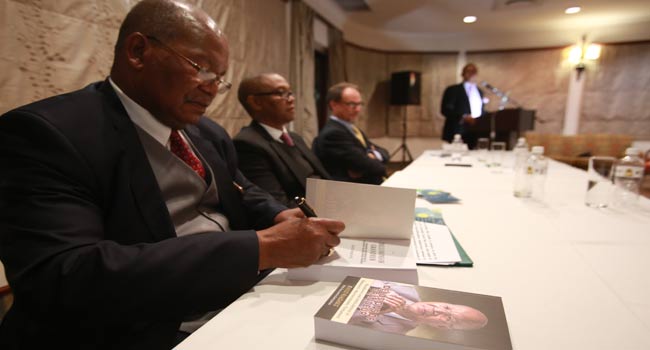

I distinctly remember that this was once a raging topic as I knew someone who worked as an engineer at Water Utilities in those days; who would periodically express strong views on the subject. Like Mogae said, the concept of a privately-owned township was a strange animal and some people in positions of power could have been hostile to the idea for all sorts of reasons – perhaps even out of outright jealousy (as Magang did indeed imply in his autobiography The Magic of Perseverance) when the idea took off extremely well and the township rapidly became a highly sought-after residential and business area, thus rendering the Magang family prominently wealthy.

Why did the idea take off so well? I remember that when I was doing my A-Level Geography project several decades ago, the topic I chose was to study the urban structure of Gaborone and to determine whether it was organic or planned, and if planned after what model it was patterned. My conclusion, if I correctly recall, was that it followed the Swedish model of Christaller who insisted on two main aspects to town planning: firstly that blocks of residences must form regularly spaced satellites around a commercial area such that distances to the local shopping centre are reasonable, and secondly that a social mix is maintained whereby a high-cost area should locate next to a lower cost area to avoid a situation whereby an apartheid of sorts is engendered between residents.

Gaborone, initially, had two distinct areas: the high-cost area basically to the north end of the Main Mall euphemistically called “England” as it was an area dominated by expatriates, and a lower cost area to the south which had its own mall called “African Mall” – so-called as it was rather more modest and was populated mostly by ordinary Batswana civil servants. Further on southward resided the less well-to-do. Even the road between the Mall and “England” was officially named “Queen’s Road” and the one between the Main Mall and the African Mall satellite area was named “Botswana Road”.

For ordinary Batswana, especially those residing further south of the African Mall satellite area, venturing into “England” must have been an eerie experience. As time went on, perimeter walls started appearing around most residences there (they were initially constructed, I believe, to protect privacy especially in houses that had swimming pools) –soon followed by numerous “Beware of the Dog/TshabaNtsa” signs as, evidently, the relative social polarisation prompted a number of burglaries in “England.” Unsurprisingly, people started calling the area “TshabaNtsa.”

As the Christaller pattern took hold – perhaps partly in response to the growing seeds of social polarisation – Self-Help Housing Agency (SHHA) residences, which were often unfinished, very modest, and mostly in the form of a “two-and-a-half” structure that was basically patterned on the domestic quarters of the well-to-do areas, began to appear next to the new posh and middle-income areas. The time was ripe for “white flight” – a well-known phenomenon whereby white residents feel uncomfortable next to mostly-black, lower income people. It was indeed “white flight” that initiated places like Sandton in Johannesburg, South Africa as apartheid crumbled and other races started encroaching into former strictly-white areas. Now Sandton has a significant proportion of affluent blacks, so it remains a thriving area of mixed races.

Phakalane is often called “the Sandton of Botswana” with good reason. Magang’s idea hit on a time when pressure on land was beginning to constrain expatriates’ preferred area of residence. Phakalane cleverly projected a promise of a certain minimum standard of housing and quickly became popular with expatriates. Affluent Batswana also joined in droves and the township grew into a beautiful residential area – helped enormously in this case by the Magangs meticulous attention to detail. But the concept of a private township in a freehold area evidently did not sit well with some and his book portrays a protracted and often-acrimonious battle with authorities to get anything done that required their approval – as was the evident case with Water Utilities. According to the gist of Mogae’s corrective letter, the corporation’s demand that Phakalane pay for basic infrastructure amounted to criminal extortion because they were getting something free that they stood to benefit from.

Was there a better way in which Water Utilities could have approached the matter? Every resident of Botswana is of course entitled to water. It is a basic human right. Even informal settlements like Old Naledi that were eventually recognised because of a significant population are catered for in this respect. It might not be good enough to insist that “Magang should have thought about utilities when he went ahead with building a township in his private land, so it is his problem, not ours”. But as Mogae observed, perhaps Phakalane Estates should have spent more effort in educating authorities about their concept and negotiating with them. But then again, how much “education” does one need to understand the Phakalane concept? For authorities, it was a case of either expressly forbidding it from the outset or being resigned to it – not something halfway between.

In any case, water is not the only necessary utility required to make the township function as desired. One also needs electricity. What is the adopted practice with the Botswana Power Corporation? As I understand it, someone who wanted electricity in an area where there is considerable distance from the nearest point of supply had to foot the bill for the cable – and the amount, of course, was in proportion to the distance from the point of supply. But if other residents then draw their electricity supply from the now-nearer points of one’s cable and accoutrements, what they are charged is not all kept by the corporation but is used to compensate the one who first established the line. As I said, that is how, I understand, it works at present – but it seems not to have always been that way: in my student days I remember a fellow student mildly complaining that Mochudi residents in the vicinity of his parents’ house took advantage of their cable and drew their electricity for much less cost.

As Gaborone continues to expand northward, it is inconceivable that Water Utilities would ignore the Phakalane pipeline as a reticulation point and construct new pipelines directly from other points in Gaborone. In that case, it would mean that the corporation is using Phakalane infrastructure for its own ends without any compensation to the Estate. Yet, I doubt if Water Utilities would allow Phakalane Estates to impose a levy or surcharge on its residents’ water bills to help recoup what must have been crippling cost even for a thriving enterprise. The fact that Magang appears resigned to the situation was probably a case of “let sleeping dogs lie.” You don’t want to antagonise a powerful institution like Water Utilities if you can avoid it. All that is left now is for one to decide whether ethics flew out of the window in Phakalane’s case, or even whether the corporation’s actions, as a monopoly, amounted to outright extortion.

L.M. Leteane