Gazette Reporter

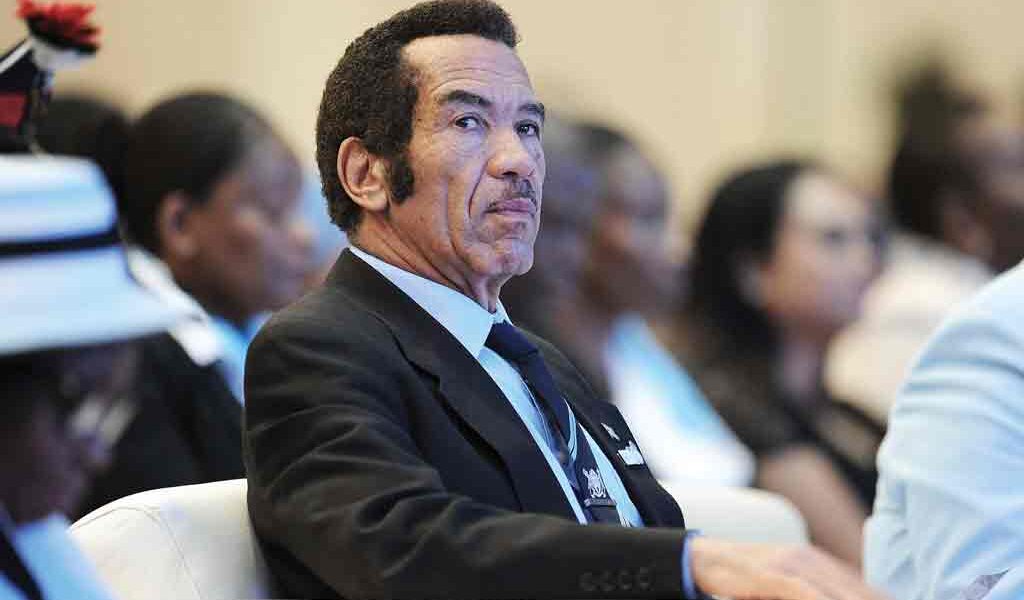

In his final address to the Heads of Diplomatic Missions, on March 13, 2018, President Ian Khama took the opportunity to issue a parting salvo to the international community. The imposition of the death penalty, according to the outgoing president, is a matter of criminal law and Botswana’s sovereign right.

The President in his speech committed his successor current Vice President Mokgweetsi Masisi to an unwavering dogma that conflicts with Botswana’s foreign policy objectives. The Botswana Gazette looks at Government’s position on an international platform against those at home.

Khama has been a staunch advocate for the International Criminal Court (ICC) and under his mentorship the country’s foreign policy has supported the international obligations and treaties that gave rise to the court, in apparent contradiction to his policies at home. Addressing Parliament in November 2015, the president stated that “Botswana further remains committed to the International Criminal Court and international Criminal Justice system. We will continue to support the ICC and cooperate with its operations.”

The commitment to the international Criminal Justice System however does not appear to extend to abolishing the death sentence and upholding the country’s human rights obligations under international law.

The ICC recognizes in its founding document, the Rome Statute that the death penalty is inconsistent with international human rights standards. According to the ICC, imposing the death penalty does not act as a deterrent against human rights violations. Instead the ICC hold that human rights abuses are deterred by “the entire criminal justice process from investigation, followed by prosecution, trial, delivery of the judgement, sentencing and punishment. The publicity associated with a trial will have an additional deterrent effect.”

In spite of his support for the ICC, Khama’s address to foreign diplomats last week was in stark contrast to the ICC’s position. Khama noted that “Botswana maintains the position that the issue of the death penalty is a criminal justice issue and its application on the most serious crimes is the sovereign right of individual States. It is important to note that the death penalty is not imposed arbitrarily in Botswana. In short, the application of the death penalty follows a thorough and exhaustive legal process that meets the basic standards of a fair trial, and the penalty is imposed for the most serious crimes as understood under international law. In this regard, as Government, we do not intend to either abolish the death penalty or impose a moratorium on its application.”

Botswana has signed and ratified both the United Nations and the African Union’s instruments on Human Rights. While both instruments accept individual states’ having the right to impose the death penalty they place limitations of a states sovereign right to do so. One such limitation being that all persons who have been sentenced to death are entitled as a right to apply for clemency and that such procedure must be fairly adjudicated. International law provides, for example, that each case for clemency must be considered on its individual merits.

A country that violates its obligations and rules of international law, other states will intervene and may file a complaint against the offending state party to the ICC. The issue of state sovereignty becomes limited.

In 2015 attorneys Martin Dingake and Joao Salbany challenged the lack of a Prerogative of Mercy hearing as well as the lack of transparency in the process, on behalf of death row inmate Patrick Gabaakanye. The Attorney General had advised Gabaakanye that if he did not to make representations a clemency hearing would not be convened to hear his matter. While a strict reading of the Attorney Generals representations showed that they violated the constitution, the Court of Appeal however, despite the wording of the letter, held that the Attorney General could not have written it intending it to be in violation of the Constitution. The Court further held that the Prerogative of Mercy could formulate its own procedures. The court declined to lay down safeguards and a minimum standard for the prerogative of mercy hearings.

On a national level, Khama has relied on the partial immunity he enjoys under the Constitution. In both the Motswaledi case and more recently in respect of investigations against his alleged abuse of office in the developments of his private property in Mosu. In the Mosu case the Ombudsman extended this immunity to cover the president even from investigation. Under the Rome Statute a sitting President is stripped of immunity and can be brought before the ICC on charges for crimes against humanity, where a national court is unable or unwilling to make a determination. The question of state sovereignty once again does not apply.

In a government statement dated October 26, 2016, Minister of Foreign Affairs Pelonomi Venson-Moitoi said “Botswana is convinced that as the only permanent international criminal tribunal, the ICC is an important unique institution in the international criminal justice system. Botswana therefore wishes to reaffirm its membership of the Rome statute and reiterate its support for a strong international criminal justice system through the ICC.”

Speaking to Reuters during her campaign for AU chair in 2016 and in response to South Africa announcing that it intended to withdraw from the ICC, Minister of Foreign affairs called for reform to the ICC to be done from within. “I don’t see why we should be pulling out. The good thing is that a few more members now, within the AU, agree that pulling out is not the solution. We should be working towards fixing.”

According to Venson-Moitoi in the same interview, she argued that while Botswana recognised the sovereignty of member states, she would, if elected, demand answers from leaders whose internal abuses of human rights called for them to be held to account. The comments were perceived as an affront to members of the AU, where interfering in a member nation’s internal affairs remained “a big taboo”, according to the Reuters report.

The South African Government, has sought to withdraw from the ICC on the grounds, amongst others, that its sovereignty has been undermined.

Khama has firmly established Botswana’s policy on the death penalty without the national debates and public awareness campaigns that the country has undertaken to engage in, and is receiving funding for by both the AU and the UN.

Government can not on one hand call to uphold international principles of human rights only to abandon them when it is expedient to do so. Will government withdraw from the ICC if (and when) a president is called to appear before it while still in office? Vision 2036 calls for a respect of human rights, do we as a nation apply our own standards or do we apply what we claim we adhere to internationally?

The ICC was hailed by the then United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan as “a giant step forward in the march towards universal human rights and the rule of law.”