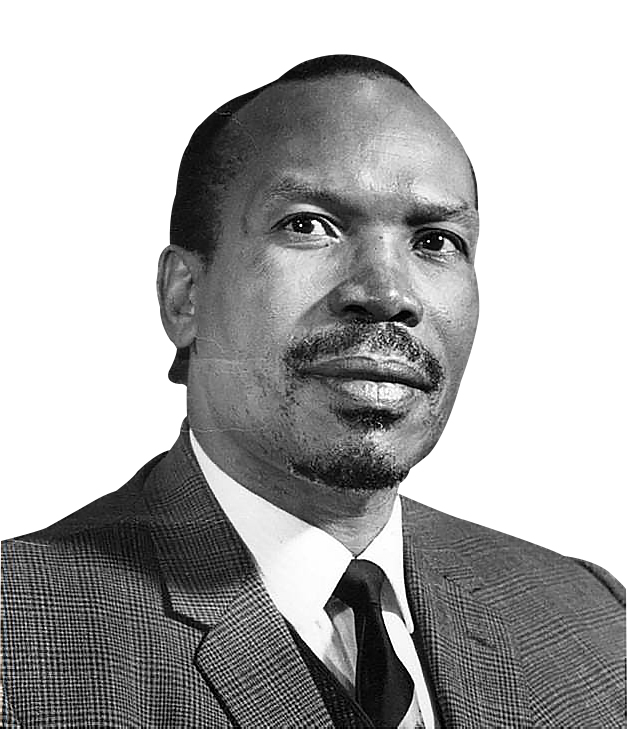

It is an open secret that Botswana’s founding president, Sir Seretse Khama, did not want his eldest son Ian to ever become president of the country.

He is famously said to have told BDP party elders and stalwarts such as B.C. Thema and Englishman Kgabo that his son was unfit to be a democratic leader by both education and temperament, and that his experience in the army had only reinforced his autocratic and repressive personality.

Although he had inherited the BaNgwato chieftainship by birth, Seretse also made no secret of his opposition to continuation of chieftainship in an independent democratic Botswana which he considered promoting tribalism and division.

And although no pan-Africanist like Kwame Nkrumah, Seretse spent much of his young adult life after the Second World War in London and was exposed to the forces of decolonisation that brought independence to the Indian continent and increasing demands for independence of Europe’s African colonies.

His political views were also heavily influenced by his treatment by the British colonial government, and the elders of the Ngwato tribe over his marriage to Ruth Williams which led to them being exiled and banned from the country of his birth for six years until he renounced his rights to the chieftainship.

One only has to read his letter to BaNgwato to understand his bitterness against not only the British but also the tribal elders led by his uncle, Tshekedi, to understand Seretse’s antipathy towards chieftainship, tribalism and autocratic rule.

It is no coincidence that during the negotiations for an independence constitution, Seretse demanded a democratic form of government based on universal suffrage with significantly reduced roles for the institution of traditional chiefs. Although the independence constitution may have been derelict in not identifying all tribal entities to be represented in the House of Chiefs, it did not single out BaNgwato for any special primacy that could legitimise tribal dominance.

It is also no coincidence that two of the first laws enacted in independent Botswana were the Chieftainship Act and the Tribal Land Act, which further eroded the influence of hereditary rulers and sought to break tribal boundaries by granting Batswana land rights anywhere in the country, irrespective of tribal allegiance.

Nor is it a coincidence that Seretse continued to combat the influence of chiefs on politics when he told Kgosi Batheon II that he had to choose between politics and chieftainship when the irascible traditionist joined the BNF in 1969. He also acted against Kgosi Linchwe II of BaKgatla who was dabbling in BPP politics, giving him the option to represent Botswana as Ambassador to the United States to get him out of politics.

If he had lived, there was no way that his soldier son would have been brought into the BDP which has led to resurrection of autocratic rule and tribal divisions, seeking to promote the myth of Ngwato supremacy. Opening Tsholetsa Club in 1977, Sir Seretse said:

“History has shown that a leadership which divorces itself from the people is a leadership devoid of wisdom. Dictatorships and tyrannical systems of government are hatched in the minds of men who appoint themselves philosopher kings and possessors of absolute truth. In Botswana we have made sure that the will of the people is supreme and those who are in government are there with the clear consent of the governed.

This has been the source of our strength, not the self-centred whims of a self-appointed man of destiny.”

All Batswana must heed these words and oppose those who seek to turn back the clock to return Botswana to the dark ages of dictatorship and ethnic division.