- Childline Botswana challenges government to release asylum seeking children held at the Francistown Centre for Illegal Immigrants

- No access to basic education

- Their health is being compromised

- Vulnerable to violence, including sexual violence.

Chedza Mmolawa

Since 2017, the government of Botswana has been in a tug of war with refugees detained at the Francistown Centre for Illegal Immigrants (FCII). The refugees have received support from private legal practitioners and international human rights agencies to launch legal challenges against their volatile detention under prison conditions where they are held together with their minor children.

In May this year, Childline Botswana, in alliance with Skillshare International, BONELA, and Kagisano Society Women’s Shelter wrote a Position Paper to the parliamentary committee on the Foreign Affairs, Defense, Justice and Security condemning the detention of children seeking asylum at the FCII.

The Francistown Centre for Illegal immigrants was initially established to act as a detention facility for illegal immigrants while they await repatriation, deportation or to be housed in refugee camps. FCII has become home to hardened, convicted criminals and those waiting for trial on a variety of charges, including serious offences. Last year the public was made aware by an INK Centre for Investigative Journalism that the prison also accommodates children and families of asylum seekers.

In the Position Paper to the parliamentary committee, Childline Botswana registered their concern regarding the children’s survival, development and care at the Francistown Centre for illegal Immigrants who have been detained there for over 3 years, “This detention has resulted in gross violation of the rights of the children which threaten their ability to grow, contrary to the provisions and principles prescribed by both local and international child protection Statutes, Treaties and other instruments such as the Botswana’s Children Act (2009), the African Charter on the Welfare and Rights of Children and the United Nations Child rights Convention,” reads the Paper.

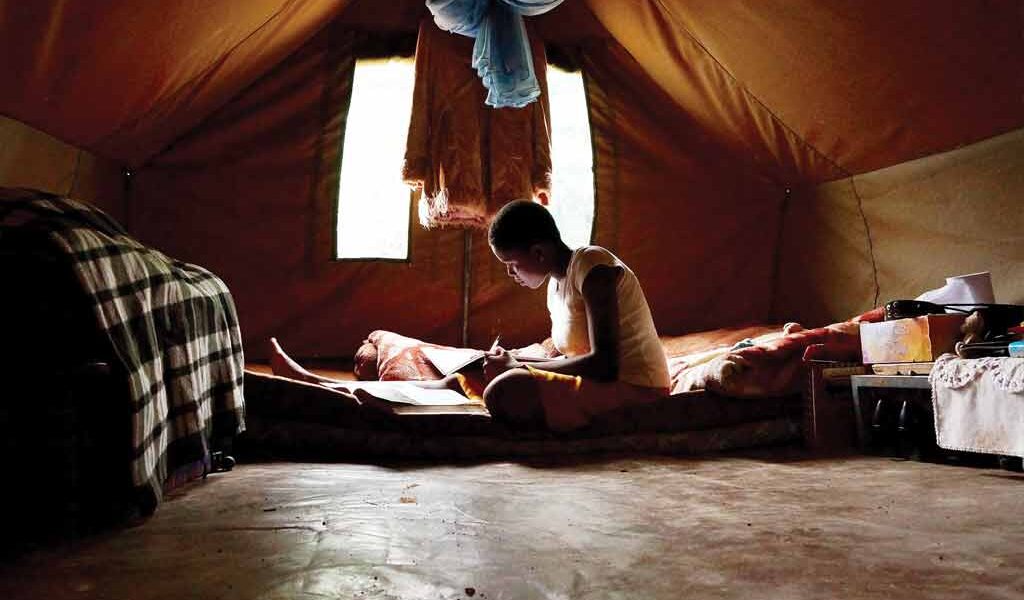

Childline and its co-authors state that the children have become vulnerable and have not had access to basic education for over three years, that their health is being compromised and that they are vulnerable to violence, including sexual violence and abuse.

The Position Paper found that while the asylum seekers were awaiting their status determination, the process took more time than the mandated 28 days prescribed by the Refugee Act. After assessing the claims for asylum seekers, which are often done in groups, not individually as required by law, the government of Botswana rejected almost all the applications for refugee status. Out of approximately 500 asylum seekers, 270 were children, “They have been detained for three years now, and in 2017, a case of sexual assault relating to one boy child was reported and investigated,” says one private attorney. Practitioners suspect many such incidents go unreported due to intimidation and at times, shame. The incident itself, is an indication of the harm the children are exposed to.

In light of this reality, asylum seekers have sought the intervention of the courts against perpetual detention. Three cases were tried by the High Court of Francistown and it declared the detention to be unlawful and ordered immediate release. As a result, more asylum seekers instituted class action against the government. The Francistown High Court, ruled that the continued detention to be unlawful and ordered immediate release. After several applications to circumvent the immediate release of the asylum seekers, the government released some who were party to the class action and refused to release those that had not been party to the suit.

Government appealed the ruling after releasing the asylum seekers and the Court of Appeal found that government was within its right to perpetually detain the asylum seekers. The Court of Appeal found that contrary to the High Court findings, the FII was not a prison camp. The decision has been widely criticised internationally.

Following the Court of Appeal decision government resolved to move, all asylum seekers that had been released to Dukwi refugee camp due to the court case, back to the FCII. (While in Dukwi most of them managed to flee the country). “The Court of Appeal has therefore essentially determined that the asylum seekers be detained indefinitely. It has in effect provided for the now 70 children to be at risk of never enjoying their right to education or living life with a semblance of normality,” lamented a private attorney.

Childline Botswana argues that the Botswana Children’s Act specifically makes mention of refugee and displaced children as part of “children in need of care”. The definition of a Child in Need of Care offers them full protection as provided for within the Act. “It therefore goes without saying that the children at FCII ought to benefit fully from the protection of the Botswana Children’s Act.” Section 18 (1) of the Act provides that every child has a right to basic education. The act covers asylum seekers and accordingly asylum seeker’s children have a right to basic education. Whilst Section 53 of the Act provides that the Minister shall provide or cause to be provided for refugee and displaced children, such basic social services as are necessary for their survival or sustenance. The Children’s Act specifically provides that its provisions supersede all other law in respect of children.

In conclusion Childline Botswana made recommendations to the Ministry to recognize “the family” as the most important unit for the care and protection of children and called for the release of all women with children (biological or under their care) to the Dukwi Refugee Camp. Childline urged government to take the opportunity to re-evaluate their refugee status and determine their applications on an individual basis and not as a group or groups. “The re-evaluation should solely be based on the best interest of the children.” They recommend that the children should be placed in alternative care during the process of re-evaluating the refugee status but note that if it is determined that they cannot be granted refugee status, a process of resettlement should be started, taking into consideration the best interest of the child.

Childline also recommended that the children be granted access to education and recreational activities while held at FCII and that the committee should visit the facility to gain first hand experience of the conditions under which the children live.

Speaking to The Botswana Gazette, Childline Botswana Coordinator and author of the Position Paper, Olebile Machete, he said since they submitted the paper to the committee in May this year, but have not received a response to date. He said before they submitted the Position Paper, they addressed the Parliamentary Committee in person and they were re-assured that they will get a reply to their recommendations. “I confirm that we submitted the position paper. We are currently continuously engaging various government departments concerning the matter. But ultimately all we can do is try to remind them of our submissions; however everything lies with the ministry. I have hope and will not give up on our recommendations being met. I can’t really say whether or not we will take further legal action in the long run or not, for now all we can do is wait. Like I said it’s a continuous process,” he said.

The Minister of Defence, Justice and Security, Shaw Kgathi said it is important for people to understand that the children at FCII are not detained. He said the correct term is that the children are held pending their relocation back to their countries of origin. “As a matter of fact, it was only last week that I was speaking to the Minister of Defence of the Democratic Republic of Congo and he was telling me that they are finishing up the process necessary to bring the immigrants back into their country of origin. For the past 3 years the Congo government has been delaying to take (sic) their people back, we have not been deliberately holding the immigrant’s captive.,” said Kgathi.

Kgathi added that as the minister responsible he has not seen the Position Paper submitted to the parliamentary committee by Childline Botswana because he does not sit in the parliamentary committee.

The Botswana Gazette also spoke to Morgan Moseki, of M.C.M Moseki Attorneys about the detention of the young children at the facility. Moseki represented some of the immigrants who lost their case at the Court of Appeal in 2017. “I am aware that there are still children at FCII but unfortunately they were not my clients at the time. They did not seek legal counsel because they said they did not want to brush up with the law the wrong way. It is very disheartening that children should be detained in a prison with criminals. I challenged the lawfulness of their detention at the Court of Appeal last year, but the judge said even though he recognizes FCII as a prison, the fact is that he cannot separate the children from their mothers and hence the reason the children are detained in an adult prison.”