gazette reporter

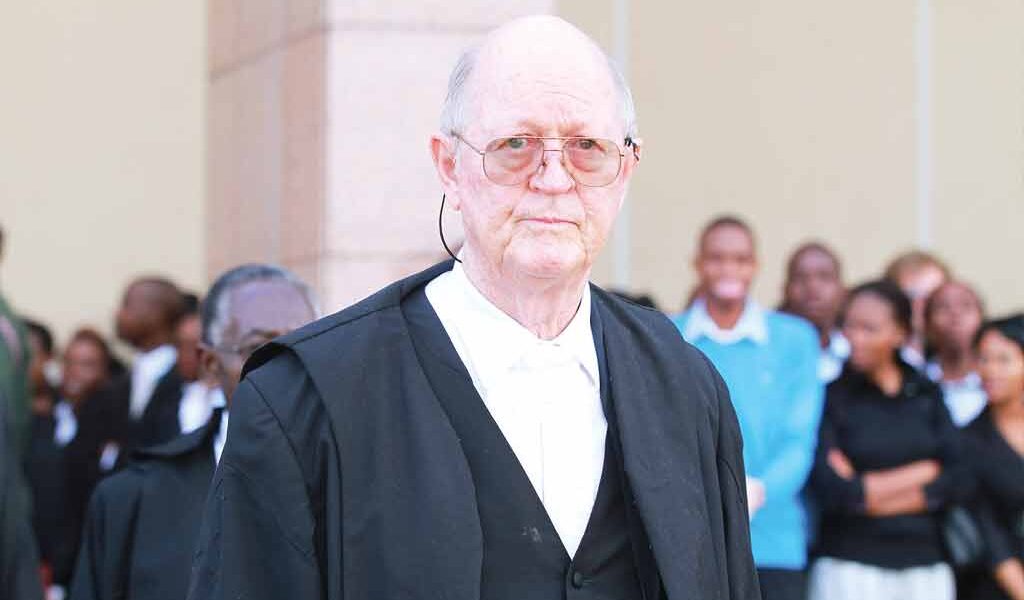

The opening address of the Court of Appeal (CoA) by Judge President Ian Kirby marked a fundamental change to the Court of Appeal’s previous findings that Botswana has been a model of democracy in Africa.

Kirby’s remarks, which he states come in the wake of media criticism of the bench being “executive” minded depart in their recognition that the underlying tenet of a democratic state, the separation of power between the executive, the legislature and the Judiciary does not exist in Botswana.

Speeches by the heads of the judiciary, the Chief Justice or the Judge President, do not have the force of judgement, they are however, indicative of the direction the legal understanding on an issue that the court seeks to adopt and a common thinking within the bench. Such speeches are of considerable importance in this regard to litigants and the public at large.

Kirby, in seeking to distance the court from criticism of being “executive” minded stated that “In Botswana there is no real separation between the executive and the legislature” adding further that the only real separation that exists is between the judiciary and “those two putative branches of government (the executive and the legislature) who are effectively one”, redefines the role of parliament and the civil service as being an extension of the political government of the day headed by the executive, regardless of which party comprises that government. The underlying and necessary concept stated by leading constitutional jurists of “preventing the government, the legislature and the courts from encroaching upon one another’s province” required for a democracy is consequently, according to Kirby’s interpretation, inapplicable in Botswana due to the manner in which the constitution is framed.

In this speech, Kirby goes a step further in respect of the judiciary. Having already stated that the executive and the Legislature are “effectively one,” Kirby emphasises the need for the judiciary to be independent stating “the judiciary which must remain independent and free of political influence, whichever party is in power. This is notwithstanding the fact that in Botswana, as in virtually every other country in the world it is the legislature and the executive – the powers that be – that in the final analysis legislate for the selection of Judges”. In terms of The Judge President’s position that the executive and legislature are “effectively one,” such legislation therefore that may be enacted for the appointment of judges is not free from political will but rather the embodiment of the desire of the executive who controls the legislature; a self-contradicting position.

The constitution however creates the three separate arms of government, at least on paper. Under Chapter IV of the constitution there is provision for the executive, under Chapter V, the legislature and under Chapter VI the judiciary. Under each of these constitutional chapters the three arms of government are separate and distinct. The interpretation that they are not and overlap is a legal one which speaks to the understanding of the democratic mores of the country. The interpretation given to the constitution by Kirby speaks to an acceptance that the philosophy and the national ethos of the country accept the restrictive interpretation of the constitution as opposed to an interpretation that advances the democratic ideals of true separation of power between the three arms of Government.

The departure by Kirby, of this accepted democratic ideal would certainly invoke the ire of the Executive, which has repeatedly in both national and international fora, reiterated Botswana’s dedication to internationally accepted democratic principles in the oversight role of the three arms of government. In this context, Kirby can be seen to be reaffirming the independence of the bench and distancing himself from being “executive” minded. However, the speech must be placed in its current context.

On the 16th January 2017, the Court of Appeal is set to hear an appeal by the Law Society and Motumise against the president that is, the executive. The Law Society’s challenge is directed specifically at the interpretation of the separation of power between the three arms of government and the authority of the executive in appointing members of the judiciary. The executive, through the Attorney General argues that it is the discretion of the executive to appoint whomsoever he chooses, to the extent of ignoring the advice of the Judicial Service Commission. Kirby’s comments in respect to the lack of separation of power between the three arms of government, reaffirm the determination already made by the High Court in favour of the executive; that the executive has the absolute power to appoint judges of its own liking.

The paternalistic, if not condescending labelling of an “executive minded” judge as a result of whether litigants have won or lost their cases is a further startling revelation by Kirby. The principle of being executive minded traditionally implies a judge that “prefer(s) a construction which will carry into effect the plain intention of those responsible (for the legislation)”. Kirby’s view that “our responsibility, whatever our personal views may be, is to respect and interpret the laws passed by the government of the day, and to ensure that these do not stray beyond the boundaries set by the constitution,” is one of sound principle when applied to legislation enacted by the “effectively one” executive and legislature. In interpreting constitutional provisions, however, as the Court of Appeal has stated on numerous occasions, the court has an obligation to look at a much broader set of rules, including Botswana’s accepted principles of democracy, international obligations and “enlightened judgements” from courts internationally.

The constitution provides that the appointment of judges shall be made by the executive “acting in accordance with the advice” of the Judicial Service Commission. The dispute that is before the court, and what the Law Society will have to convince the court of, is that while the legislature may make laws for the appointment of judges, the executive plays a ceremonial role in such appointment; that the executive executes the appointment of those candidates referred to him by the Judicial Service Commission and does not make a determination of the actual appointment, the executive must act in “accordance” with the advice. The Law Society will seek to convince the court that such a position is in conformity with the internationally accepted principles of judicial appointments in a democratic society such as Botswana has always purported to be. The position adopted by Kirby in his opening speech, directly conflicts with this argument while seeking to retain the position that the court is not “executive” minded.

At the heart of the complaint of being labelled “executively minded”, as well as at the centre of the pending litigation in the Motumise case, lies the constitutional concept of judicial independence. Judicial independence is the cornerstone in the public’s faith and trust in the judiciary, it is the public’s guarantee that a judge will be impartial. Judicial independence is not, as it is normally (mis)understood to be, an ideal that accrues to the benefit of the judge.

Importantly it is judges who are responsible for the preservation of this ideal and the independence of the judiciary. The Chief Justice and the Judge President, having important constitutional and administrative roles are required to act as a buffer between the judiciary and the executive, but it is incumbent on all judges to be vigilant to preserve their independence. Government and all others must be kept out of a position of exerting influence, directly or indirectly on the court. The independence of the judiciary, just as with the separation of power are fundamental principles of our constitutional democracy.

The democratic principle that underlines the separation of powers entails that, in the case of the legislature, responsible for the enactment of rules of law, it may not be involved with the execution or with judicial decisions concerning such enactments. Similarly, with the executive, it is neither empowered to create laws, though the executive brings them into effect by executive function, nor may the executive administer justice. The Judiciary, by the same token should not enact or create laws. Under the constitution, the three arms of government are separate bodies having their own functions and office. There is a legal overlap in their function, but to promote a legal position that undermines, as opposed to promoting the separation of power between the three arms of government is contrary to the established principles of a democracy.

A distinction exists between testing legislation against the constitution and how to interpret the meaning of a constitutional provision on its own. It is the role of the judiciary to protect and promote interpretations of the constitution that are consistent with the ideals, hopes and aspirations that Batswana as a whole adhere to and strive to achieve. The consolidation of executive authority, over the legislature and by extension the judiciary is certainly not one such ideal.

It is apposite to take heed of the words of Frantz Fanon; “The life of the nation is shot through with a certain falseness and hypocrisy, which are all the more tragic because they are so often subconscious rather than deliberate … The soul of the people is putrescent, and until that becomes regenerate and clean, no good work can be done.”

The current Court of Appeal session will certainly define our country going forward. Whether it will define us in a tragic manner or regenerate and clean us as a democratic nation remains to be seen.