While the parallels between China’s Belt and Road Initiative and projects of the erstwhile British Empire are not difficult to establish, it may be worthwhile to try to understand why China has been hyping up the BRI at its 10th anniversary party

DOUGLAS RASBASH

On 17 October 2023, the much-hyped summit marking the 10th anniversary of China’s Belt and Road Initiative or BRI was inaugurated in Beijing. World leaders, including Russia’s Vladimir Putin, gathered in Beijing for the high-profile event, which took place in the shadow of a spiralling war between Israel and Hamas.

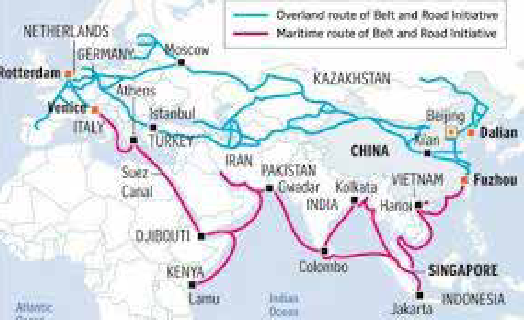

Since its launch by Chinese leader Xi Jinping in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has poured hundreds of billions of dollars to power the construction of bridges, ports, highways, power plants and telecoms projects across Asia, Latin America, Africa and parts of Europe. Yet in many ways it is a very similar strategy to the trade routes and infrastructure built by the British Empire from 1850 to 1950. The Belt – that is to say road rail and energy infrastructure – extends some 50,000 km while the road, meaning shipping lanes and ports, covers at least 20 deep sea ports.

The British Empire built railways and ports in all the territories over which it had domain and for the same reasons – trade. Some 120,000 km of railway and over 100 ports were built in 57 territories between 1850 and 1950. The British version of BRI even built the Shanghai–Nanjing Railway (1905–1908) and Kowloon–Canton Railway (completed 1911), as well as the ports of Shanghai and Hong Kong and Port Arthur in China.

For 70 years, the British Empire accounted for around 20% of global GDP. China’s share of global GDP has risen from 13% in 2013 to 19% in 2023. The only difference between China’s BIR and the British Empire is that Britain paid for all of the investments while China investments are loans that require repayment. One of the obvious reasons for this is the British Empire was also a political empire over non-sovereign nations and so there was no possibility of repayment, while China lends money to sovereign nations and requires repayment in full.

Considering, the BIR debt trap, analysts have characterised Chinese lending through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as “debt trap diplomacy” designed to give China leverage over other countries because it can even seize their infrastructure and resources (India Times.17 Sept 2023). Debt leverage has enabled access to the resources that China’s mighty economic machine needs in the same way that political leverage enabled the British Empire to access resources to feed its own mighty economic machine.

There is no doubt that the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative and the development of global trade infrastructure by the British Empire share certain similarities, particularly in terms of their aims to enhance trade, connectivity, and influence. Both initiatives were driven by economic, geopolitical and strategic interests. China’s BRI aims to enhance trade by developing infrastructure networks across Asia, Europe, Africa and beyond. It includes roads, railways, ports, and other facilities to facilitate the movement of goods and services. The British Empire established a vast network of trade routes, ports, and infrastructure during its colonial era to facilitate trade and resource extraction, especially in Africa, Asia, and the Americas.

China seeks to expand its geopolitical influence and secure strategic interests by establishing a network of friendly nations and improving access to crucial regions for resources and markets. The British Empire aimed to secure its geopolitical interests, gain resources, and establish dominance in global trade and commerce through its extensive colonial network.

China aims to promote cultural exchange and understanding through BRI projects, fostering deeper connections and partnerships with participating countries. The British Empire also had a significant influence on the cultures, languages, and governance systems of the territories it colonised.

Infrastructure development is a key aspect of BRI, aiming to address infrastructure gaps and boost economic growth in participating countries. The British Empire built roads, railways, ports, and other infrastructure in its colonies, often with the intent to facilitate resource extraction and trade.

The BRI has sparked debate on whether it represents a cooperative approach to international development or it is a form of neo-imperialism due to China’s economic and geopolitical influence. The development of trade infrastructure by the British Empire is also viewed through the lens of imperialism and its impact on the regions and countries that were part of the empire.

The enduring aspect common to both initiatives is the legacy of infrastructure. The trade routes, ports, railways, and other infrastructure established by the British Empire have left a lasting impact on the regions involved. Similarly, the BRI is likely to leave a significant and lasting imprint on the global infrastructure landscape, influencing trade patterns and connectivity for generations to come.

The British Empire’s trade infrastructure development was primarily funded by the British government and private investments to non-nation states. This investment approach had implications for global trade politics during its time, shaping colonial relationships and resource exploitation.

By contrast, the BRI relies heavily on loan funding from China, raising concerns about debt sustainability for participating nations. BRI’s economic impact from 2013 to 2023 is notable, but it has also brought about debate regarding the debt burden and its potential to depress national development in borrowing countries.

The British Empire’s trade infrastructure significantly impacted global trade and economic dynamics during its era, establishing the Britain as a dominant global trading power. The economic effects were profound, shaping commerce, governance, and societal structures in the regions it influenced.

The BRI has rapidly expanded economic connections and trade, fostering growth and development in various participating countries. However, concerns about debt sustainability and its potential negative effects on national development have become prominent. The BRI’s impact on global trade dynamics continues to be a subject of analysis and discussion, acknowledging its transformative potential alongside associated challenges.

In summary, while both initiatives aim to enhance trade and connectivity, differences in funding and economic impacts set them apart. The British Empire’s historical influence on global trade politics and economics was substantial, financed by the British government and private investments. Conversely, the BRI, largely funded by China, has brought about notable economic effects from 2013 to 2023 while sparking concerns regarding debt sustainability and potential dampening effects on national development in borrowing countries.

Economists have yet to compare the BRI and the British Empire, but indebting partner countries in the BRI may one day prove to have been a mistaken strategy. Given that China’s economic growth is already showing signs of faltering after 10 years while that of the British Empire lasted almost a century, it is unlikely that the impact of the BRI will be as significant.

Perhaps that is why China is going to such great lengths to hype up the BIR at its 10 anniversary party.