How our propensity to believe shaped society

DOUGLAS RASBASH

Don’t worry, Homo Credentis is not a new species of Hominid that will wipe us out in 250 years-time, but an invention of the author, a totally new and unique term that may gradually gain credence as it spreads – following this World exclusive in the Botswana Gazette. If you Google ‘Homo Credentis’ you will not find it – so this is a Universal first.

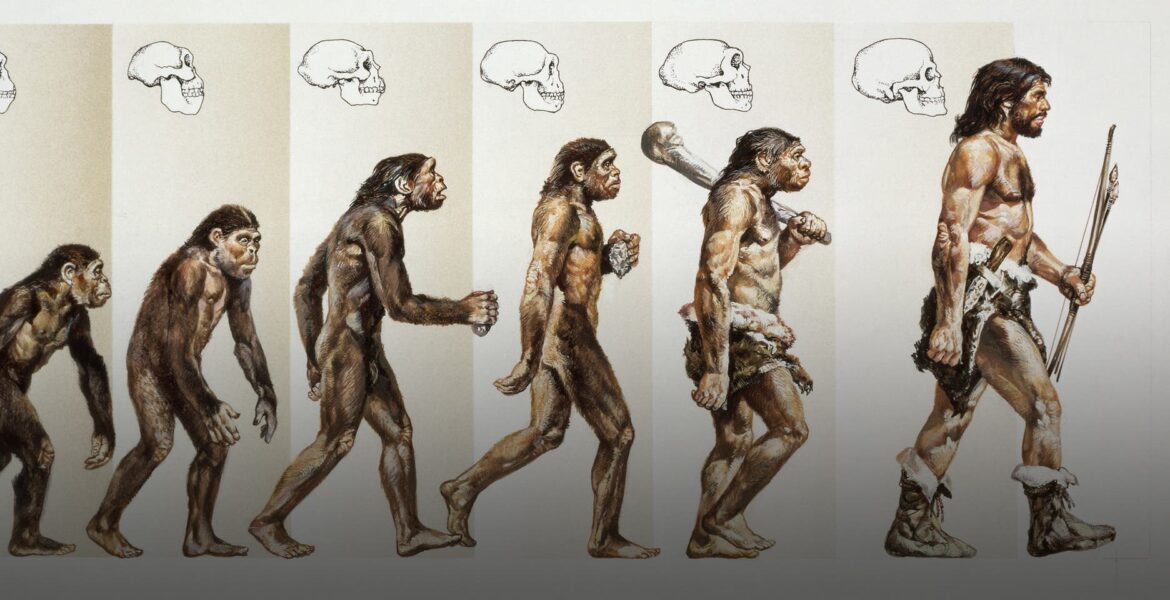

Homo Sapiens

Let us ask this question; is our scientific name apt – is the appropriate, the right name for our species? Homo Sapiens the wise one, thinking one, knowing one, was coined by Linnaeus in 1758 at a time when we considered ourselves superior to other life. That was one hundred years before Charles Darwin published The Origin of the Species in 1859 that proved that all life evolved and was interconnected. Our scientific name may not just be arrogant but actually inappropriate. The feature argues that what humans do best is to believe and to not know. We hope, we trust, we have values and our social structures are not based on common knowledge but common beliefs.

Other hominids

Like Sapiens, other hominids knew things too, but their species did not endure. Sapiens did because they believed. Without common values and beliefs, Sapiens would have surely died out, we would not have evolved into large organised, cooperative groups. The last hominids, Neanderthals did not believe so they could not form into large groups, so they died out. Thanks to the unique gene called vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VAMT2), Sapiens are predisposed towards spiritual or mystic experiences. Because of this the VAMT2 gene is also dubbed the God Gene – without VAMT2 Sapiens would not believe in anything – including God.

Sentient questions

Let us go deeper and further. The questions that drive our existence are those that all sentient beings ask; what, how, who, where, which and when. What food can be eaten, how do we catch the food – hunt it, browse it etc; Who is my mate or clan member? Where is my shelter? Which direction is the water hole and when is it time to migrate to greener pastures? But there is one question deliberately missing in this, and that is ‘why’. Let us hypothesise that only Homo sapiens ask why. A dog doesn’t ask why it needs to sit or walk to heal. Nor does a cow care a jot about why it’s being milked, or a fish ask itself or the guys in its swarm why the oceans are warming. Yet the children ask why they must sit still, eat their crusts and go to bed at 7 pm.

Compunction to ask why

So, the defining feature in Homo Sapiens is the compunction to ask why. Why is an abstract question which does not help us to survive, but to understand and to progress. Asking why promulgates belief and faith because sapiens, until science came along, were unable to provide rational answers to life’s questions and so sought mythical answers. And even now, when surrounded by more accessible knowledge than ever in the entire evolution of life, mankind would rather believe than to know. It is extremely rare for a human to be able to set aside a lifetime of belief, even when confronted by irrefutable and incontrovertible information that counters that belief.

Accentuated differing beliefs

It possibly explains why the WWW has not united humanity in common knowledge but, arguably, accentuated its differing beliefs. When belief is confronted by knowledge – belief invariably wins. With all this in mind our species might be renamed homo credentis the believing one. This perspective raises some intriguing points about the term “Homo sapiens” and its potential implications. The scientific name “Homo sapiens” translates to “wise man” or “thinking man,” which historically reflected the belief that humans possess higher intelligence and cognitive abilities compared to other life forms. Our defining characteristic might not solely be our rationality or knowledge but also our capacity for belief, hope, and trust.

Age of the internet

Humans are inherently social creatures, and our social structures are often shaped by shared beliefs and values. These beliefs can sometimes transcend factual knowledge and play significant roles in how societies function and individuals interact. In the age of the internet and the World Wide Web, access to information has increased exponentially, but it hasn’t necessarily resulted in a unified common knowledge, or decline in religious practices and other beliefs. Instead, it has highlighted the vast diversity of beliefs and opinions held by individuals and groups worldwide. The proposition of renaming our species as “Homo credentis,” the believing one, certainly adds an interesting layer to the discussion. It acknowledges that beliefs have a profound influence on our species and our societies. It reflects the importance of understanding how beliefs can shape our actions, decisions, and interactions with one another.

Biological characteristics

However, it’s worth noting that the naming of species in taxonomy is primarily based on biological characteristics, not cultural or social attributes. The current scientific name “Homo sapiens” remains a valid and widely recognized term in the field of taxonomy. Until the discovery of VAMT2, it would not have been taxonomically acceptable to name a species based on an abstraction. Nonetheless, the thought-provoking idea encourages us to reflect on the complexities of human nature and the importance of understanding the role of belief systems in shaping our world. It reminds us that while knowledge and reason are crucial, beliefs also play a significant, arguably most significant, role in human behavior and society.

Exploitation and manupulation

While Sapiens may have had evolutionary advantages over Neanderthals, it also exposed us to exploitation and manipulation. Politicians can sometimes exploit people’s belief systems for their own gain by using various tactics to appeal to emotions, manipulate perceptions, and secure support. Politicians often play on people’s emotions, using fear, anger, hope, and empathy to elicit strong reactions. They might frame issues in ways that evoke strong emotional responses, making it easier to sway public opinion and gain support. Politicians may exploit people’s sense of identity, whether it’s related to nationality, religion, ethnicity, or other social factors. By aligning themselves with specific identity groups, they can create a sense of solidarity and loyalty among their supporters. Politicians might tailor their messages to align with people’s preexisting beliefs and values, reinforcing their supporters’ views and confirming their biases. This can create an echo chamber where individuals only hear information that supports their existing beliefs. Politicians often make promises that align with people’s desires and concerns. They may offer solutions to complex problems that sound appealing, even if these solutions are unrealistic or oversimplified. Politicians can selectively present information to bolster their arguments and omit facts that might undermine their positions. This manipulation of information can lead people to believe a particular narrative without having a complete understanding of the issue. As with hope, fear is a powerful motivator. Politicians may exaggerate potential threats or dangers to society, creating a sense of urgency that pushes people to support their policies as a means of protection. Some politicians work to build a strong personal connection with their supporters by presenting themselves as trustworthy and relatable figures. This can lead people to put their faith in these politicians, even if their policies or actions might not be in the public’s best interest. Skillful use of symbols, slogans, and rhetoric can create a sense of unity and purpose among supporters. Politicians may use these tools to tap into deeply held values and sentiments. With the rise of social media, politicians can exploit algorithms to target specific demographics with tailored messages. They can also spread misinformation or divisive content to further polarize and manipulate public opinion. Politicians might create a sense that their supporters will miss out on opportunities, benefits, or rewards if they don’t align with their ideology or policies. This fear can drive people to support politicians even if they have doubts. It’s important for individuals to critically evaluate information, be aware of their own biases, and seek diverse sources of information to make well-informed decisions. Developing media literacy skills and actively engaging in open dialogue can help mitigate the impact of politicians exploiting belief systems for their own gain. But VAMT2 enables politicians to exploit our greater propensity to believe rather than know. In the post 4IR world AI can be used to great effect to expose the gaslighting. Fact checkers are an anathema to those seeking to deceive and manipulate.

The believing one

The idea of renaming our species as “Homo Credentis,” the believing one, reflects an aspect of human behavior that might be a distinguishing factor. The identification of VAMT2, ‘the imagination or God gene,’ and the indisputable role of belief systems in shaping our social dynamics and collective behavior, are intriguing areas of research that contribute to our understanding of what makes us unique as a species. Science continues to explore and uncover the complexities of human nature, and while taxonomy traditionally focuses on biological characteristics for naming species, there’s room for broader discussions about the cultural, social, and cognitive aspects that define Homo Credentis nee Sapiens. The definition of belief is much broader than religion. Belief encompasses hope for the future, trust in Government or the value of our currency, belief in a common cause – good or bad. Humans believe in human nature, the brotherhood of man and rely on ethics and moral standards. We believe in Botswana and in the concept of nationhood. As scientific knowledge progresses and our understanding of human evolution and behavior deepens, the discussions around the naming and classification of species may evolve as well. The journey of discovery is ongoing, and our openness to new insights and perspectives enriches our understanding of ourselves and the world we inhabit. Let our species be renamed Homo Credentis and let the Botswana Gazette be credited with being the worlds’ first publication to have used the term.