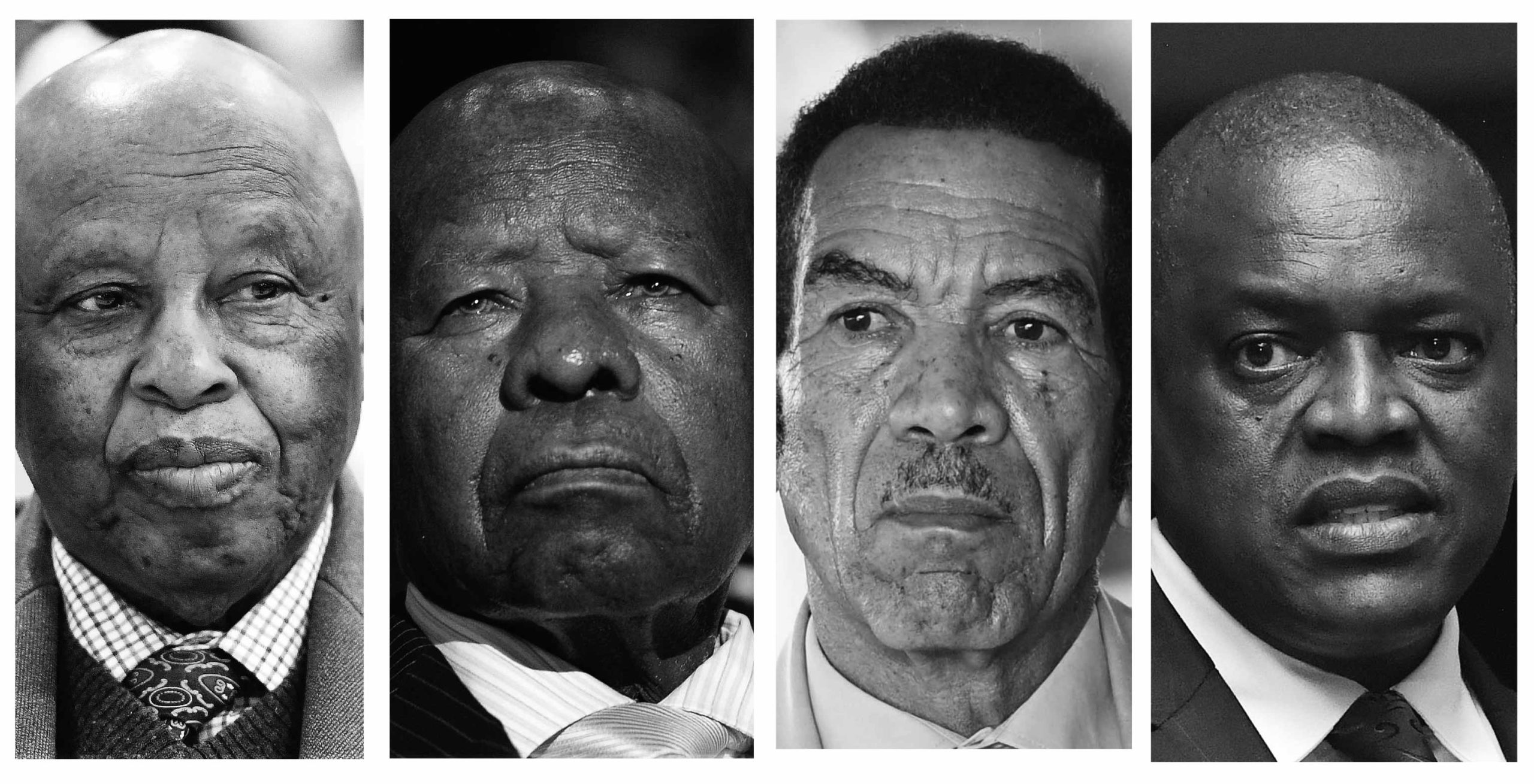

Although a nasty pong caught up with Botswana’s second president that he eventually characterised as an error of judgement, Sir KetumileMasire was clear that to dabble in private business while in office was bad for any president and his or her country. His successor, Festus Mogae, thought much the same and had advised Masire against it. However, under President Mokgweetsi Masisi and Ian Khama before him, these norms seem to be thrown out the window. Staff Writer TEFO PHEAGE illustrates the contrast

By engaging in business while in office, President Mokgweetsi Masisi ignored the norm established by his earlier predecessors and drifted the principle that a sitting president must strive to remain beyond reproach, The Botswana Gazette has established .

In his memoirs, “Very Brave or Very Foolish,” former president Ketumile Masire discusses the subject that troubles Masisi today extensively. The latter finds himself roundly criticised following discoveries that he holds shares in the controversy-ridden Choppies enterprise of Ramachandran Ottapathu. He is currently grappling in the mud with some farmers over a portion of state-owned Banyana Farms where impeccable sources say he has been among the frontrunners after violating all conditions for bidding applicants.

It is not known when and how Masisi acquired the shares in Choppies. What is known are his views, stated through his spokesman, Batlhalefi Leagajang, that there is nothing wrong with an incumbent president engaging in business because doing so is not prohibited by law.

This invokes Masire’s bookin which the second president of Botswana expressed a distaste for such conduct at pages 241 and 243. Masire held the view holding shares in private businesses is a dangerous expedition to the holder of the shares, the presidency and the country.“I never had any crude approaches,” he wrote,“but I also tried to avoid situations that held dangers of conflict of interest. For example, Satar Dada wanted me to buy shares in a new Mercedes dealership. I was uneasy about this, so I discussed it with Festus Mogae, and he too, was uneasy. So I declined. In retrospect, I am glad I did, since the dealership ended up selling equipment to the mines in Orapa and Jwaneng.”

In what sounds like a response to the prevailing view on Government Enclave position that there is no conflict in Masisi’s wheeling and dealing in private enterprises, Masire wrote: “While it was possible to have owned the shares without any element of conflict, the situation was exploitable; and that would have disturbed me, and it would have disturbed the mine-both very important things! Justice must not only be done but must be seen to be done.”

But did Masire accept ‘gift’ share offers? “I knew about a few overt attempts at buying influence,” the late elder statesman wrote.“I once was approached directly by an Afrikaner named Blacknote who offered me shares in his company free of any payment. I declined, and I explained to him that while we wanted to have black citizens participate in business, we wanted it to be on a commercial basis, not as a favour … In another case, while Lemme Makgekgenene was a minister he was approached by an Asian trader with a similar proposition. He declined and then reported it to me. In addition, no end of letters came to me over the years offering to open secret bank accounts in Switzerland, which, of course, I ignored.”

Masire noted that there was perception in many countries, perhaps most, that politicians were in the game to enrich themselves and that such perceptions had taken the form of accusations in Botswana. “One of the reasons we developed open procedures with checks and balances was to try to minimise the opportunities for abuse of influence, especially by ministers and high-ranking officials,” he wrote.

“We were both lucky and careful when we started the party. We were lucky that the first leaders of the party comprised a very honest group. They were hard working and dedicated to the service of the country. Seretse Khama set this standard by being very clear that politicians and civil servants should not see independence as a route to enrich themselves personally.

“The problem in politics arises not because people are ambitious since one should be ambitious. But when politicians selfishly want things when there is disregard for the country and for other people,or for what is reasonable,and especially when they use their political positions for personal gain,then it is not only unreasonable but dangerous for the country. These are the kinds of people of people who have wrecked other countries.”

In the book, Masire described President Masisi’s father, Edison, as an morally upright man “who once discovered that management of the BMC was staying in a first class hotel in Rome and went to them and told them to move to a less expensive hotel,such as the one in which he was staying since the money they were spending belonged to the farmers of Botswana”.

According to the book, Masire was clear in his view that when people are elected to office, it is wrong for them to enrich themselves from their position. However, and inspite of this, Masire once attracted vitriolic criticism when it was said two bailout schemes designed by De Beers were really meant to rescue his company, GM Five, which was deep in debt. But in all fairness to Masire, the controversy occurred when he was no longer president.Even so, there had been one pong that happened when he was in office that Masire found difficult to wriggle out of. It entailed a loan programme purportedly put together to finance his Gantsi farm manager’s employment. In the end, with egg on his face, President Masire admitted that it was an error on his judgement.

“With the perfect vision of hindsight, I would not now enter into such an arrangement,” he wrote in a press statement. “Beyond the fact that it would not conform to today’s more rigorous guidelines for good governance, which I fully embrace, its outcome was also an object lesson for me in the pitfalls of trying to manage a commercial farm by remote control. In the end, I had to cut my losses by leasing my properties until I finally retired from office. Here I am reminded of the adage, ‘While good judgement comes from experience, experience is often the product of bad judgement.”

Masire’s successor, Festus Mogae, an economist whom Masire said had advised him against buying shares while in office, delved into in business post his presidency. However, Mogae’s public image was muddied by his association with Ram of Choppies. This is the same man that, in what many see as a slap on Mogae’s face, President Masisi has embraced. Mogae is currently on his way out of Choppies shareholding after accusing Ram of being everywhere at Choppies and stifling institutional governance by bringing his financial muscle to bear on other directors.

This week Mogae told The Gazette that he “was not aware that Choppies was trading with a company that was co-owned by President Masisi and Ramachandran Ottapathu.”

Can one survive on the presidency alone?

In his memoirs, Masire wrote that public officers “must not be paid as paupers;otherwise,we would not get people who can deliver the goods”. He continued: “I am not in favour of lavish standards, but we must be careful that our political leaders don’t trail too far behind successful individuals in the rest of society.”

Although Botswana presidents rank less than most of their peers in salary, they are comfortable because they are reasonably rewarded even beyond retirement. And now, thanks to the man from whom Masisi took over, they can now seek employment without forfeiting their considerable drawings from the state. Some of these benefits are extended to their spouses.

Of all Botswana leaders, the founding president Seretse Khama seems to have been the only one who entered the presidency broke, according to his biography written by Neil Parsons, Thomas Tlou and Willie Henderson. This may be a clear demonstration that previous struggles with money may give birth to an insatiable appetite for pursuit of wealth while in office, without impugning anything on the founding president.

Below are extracts from Seretse’s biography

Seretse was suffering acute embarrassment by October 1958. He was being sued by the builders Promnitz Brothers for €1 800 outstanding on his yet unfinished house. The banks were refusing to honour his cheques; and he was obliged to take the drastic measure of delaying the payment of his own employees.

Seretse had been relying on income from cattle sales to commercial buyers on the line-of-rail. This was to supplement, and ultimately replace, his allowance from the British government. The allowance had been fixed at the rate of €1 000 (down from €1 100, but the same as Rasebolai Kgamane’s colonial allowance) a year for five years after his return home- in other words up until 1960-61. Provision was also made for a sum of up to a maximum of €2 500 to cover the capital cost of his family’s removal and resettlement. Other capital costs – opening up a ranching business and building a new house in Serowe – would be covered by the sale of the house at Addiscombe in England. (Its value was estimated at €2 500 after paying off the mortgage.) For any further expenditure Seretse would depend on the profits from cattle ranching.

Two years after settling back home Seretse’s capital costs were over-running, and his income from cattle sales was negligible. Cattle owners in Bechuanaland were suffering from an embargo on exports imposed by South Africa and Southern Rhodesia. Ostensibly for reasons of disease control, the embargo was generally acknowledged to be motivated by protectionist ranching interests in those countries.

When he was first strapped for cash, in September 1957, Seretse got the British authorities to pay out his monthly allowance as an annual lump sum. In June 1958 he appealed for a one-off payment of the balance of all his allowance to 1960-61. The C.R.O. dallied over the issue, but agreed to pay put in October 1958:

‘As the only grounds on which we could refuse, or suggest some variation, would be that we wished to keep some control over Seretse. As Fawcus (Government Secretary)pounts out……Seretse is aware of this and has already made complaints about it.’

Seretse pressed for immediate payment of the final balance, and the C.R.O. agreed to rush payment of the remaining €2 583 by the end of the current financial year on March 31st, 1958. Before being made aware that Seretse also had health problems, a C.R.O. official had minuted; My impression of Seretse is that he is easy going and probably not very efficient in all his affairs, particularly financial.

Seretse was too ill to travel to Francistown in September 1958, to bid farewell to Sir Percival Liesching as High Commissioner. This may also have been a diplomatic counter-snub to one who had so often made clear his distaste for Botswana.

Stories spread ofSeretse reaching a peak of irascibility over his financial difficulties in November 1958. He finally broke with Peto Sekgoma, accusing Peto of having pocketed money and cattle ‘while I was in England’. Seretse was also said to be at odds with Rasebolai and with Tshekedi. Tshekedi was rumoured to be plotting against Seretse once again because Seretse was accusing him of cattle theft.