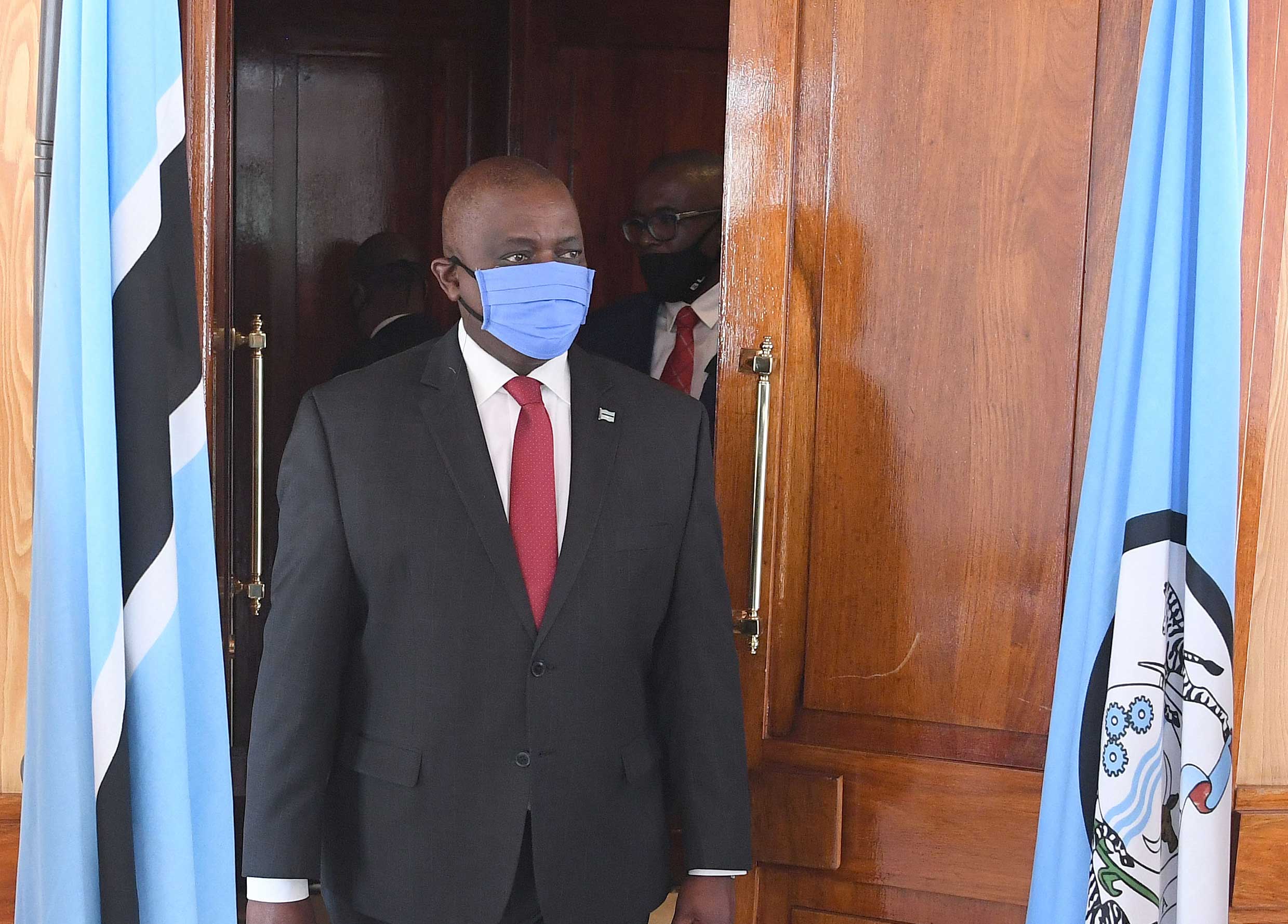

A candidate for an MA in Economic Development at the State University of Campinas in Brazil, Sthatho Nlebgwa, argues that President Mokgweetsi Masisi owes it to himself to make a clean breast of things regarding his business interests by making a full disclosure of them without compulsion of any law. Having done so, Masisi should proceed to disentangle himself from any unseemly knots because the optics are of the essence in the position that he holds and the immense power that it can wield. Otherwise the perception will gain traction that his stated legislative agenda to empower Batswana is just another ploy in a series of tricks to benefit non-indigenous citizens.

As parliament readies to receive and debate a proposed law on citizen economic empowerment, an equally important debate emerges from the shadows. And no, I am not talking of the question of who is the ‘citizen’ who is going to be empowered. Here I am referring to the incestuous relationship between business and politics. Where do we draw the line? That is the million pula question.

I recently caught snippets of an interview between the very able veteran journalist, Kealeboga Dihutso (he is going to hate me for calling him a veteran), and the President’s spokesman, Batlhalefi Leagajang. The interview dealt with reports that President Mokgweetsi Masisi was in business with one of Botswana’s most influential businessmen, the CEO of Choppies, Ramachandran Ottapathu. The snippets were telling of how this incestuous relationship manifests itself. There was an air of deafness, condescension and arrogance about Mr Leagajang. As he answered, I was reminded of Sean Spicer and Sarah Huckabee-Sanders doing their spin doctoring for the US President Donald Trump.

The debate whether presidents – or more broadly, elected officials and those who hold offices of public trust – should be in business where a conflict may arise is as old as the advent of the democracy experiment itself. If memory serves me right, in one of the early writings that would birth what is now a representative democracy, it was argued that those who assumed leadership should be people whose concern was public good with no private interests of their own. This idealism was to take away conflict of interest away from governance. It sought to have a form of representative democracy that was unadulterated by private interest.

What Mr Leagajang missed in his interview with Mr Dihutso was not whether it was legal for the President to hold business interests and be in business with whomsoever he so chooses. The point of the interview had more to do with the optics of it all, considering our economic dynamics as a country. His Excellency Masisi is not being singled out because this question obviously pre-dates him and shall continue to beleaguer experts on governance for centuries to come. The same was asked of Festus Mogae and Ian Khama over their business interests. The optics has been the main concern as confidence in political leadership often goes beyond legality but perception.

While the President may be legally free to do business with whomsoever he chooses, from a PR perceptive some business dealings may be problematic. They call into question his commitment, for example, to be a champion of citizen empowerment and to combat corruption. It need not be true, but the optics always has more sway than the reality. Of recent Choppies, which is under the stewardship of and is owned in part by his business partner, Ram, was awarded a lucrative tender to distribute old age pensions. Questions have arisen as to whether the tender was awarded in accordance with the PPADP Act or political pressure was at the core of the award. Whether it is true or not, the optics are all wrong.

We could go on and on detailing how the optics of any president’s dealings were and are wrong. What is needed is for the presidency to acknowledge the pickle it finds itself in and then do whatever is possible to rebuild public confidence in the presidency by rising above private interests. One of the most important but long overdue moves is to enact a comprehensive declaration of assets and interests’ law for all people holding offices of public trust. While our current laws do not require such disclosures, the President – for his own sake – should make a public disclosure of his assets and interests for the nation to see. This goes along with his professed ‘commitment’ to running a transparent government which he must demonstrate for everyone to see in his person first.

Another important move that the President should undertake, after making the disclosures, of course, is to set up a blind trust to manage his private dealings for the duration of his presidency. This goes a long to build public trust. Lastly, I would urge the President to divest in business relationships that bring into question his ability to deliver his promises. This is not about legality but about public trust and optics. Using the Citizen Economic Empowerment debate as an example and the question over who will benefit, the public pulse posits that non-indigenous Batswana are the intended beneficiaries. His business relationship with Ram is bad for optics and building public confidence in the proposed law.

This here is the reality of it all. Whether people holding positions of trust should be in business has never been about legality but optics. Perceptions matter in building confidence around these people and public institutions, and it is those who hold such positions that can cleanse them. The President has a responsibility to rid the presidency of the stench of perceived corruption and other negative connotations attaching thereto. He has to do so as a matter of urgency. He has at his disposal the power to influence law and policy. He has the ability to rise beyond rhetoric and take a lead even in the absence of any legislation or policy.