THE POLEMICS

Lekgowe, Mogapi & Kgosi

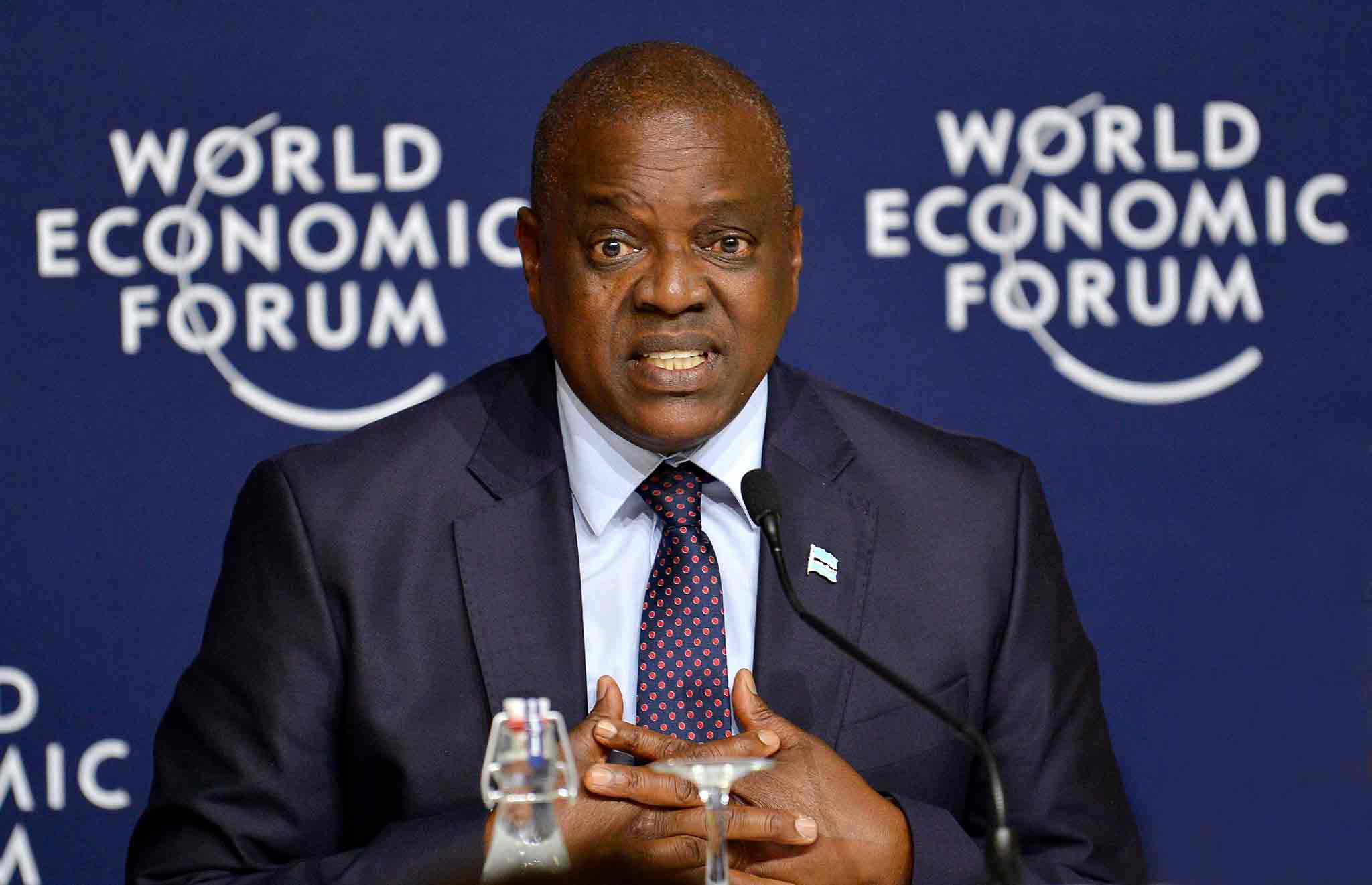

Masisi’s transformation team has a tall order in front of them that will either usher in a New Botswana or take us back to the dark times we hope to come out of.

For the past 20 years, the unemployment rate in Botswana has oscillated between 15 percent and 24 percent, according to the World Bank. At any point in that time, an average of one out of every five people in the labour force were actively seeking employment and was turned back at the factory doors and receptions. These numbers exclude all those who grew disillusioned, burnt their curriculum vitaes and left the labour market altogether – those who gave up.

In the same span of time, the economy was growing at a staggering average of 7 percent annually. If you consider that you can drown in a pool of an average depth of two centimeters, you would know that that economic growth rate has rather been shallow in reach and has not translated into any meaningful job creation.

The question then is who has been the beneficiary of all this economic growth for the past 20 years? It is not hard to tell. Soaring income inequality in Botswana, the highest in the world, explains this, meaning that only a few profit from our economic output. This, to a large degree implicates our political leadership in plunder. Whereas you can have an economy lopsided in favour of one group over another, by chance for a limited period, when the same morphs into a 20-year long pattern, it becomes apparent that the economy is rigged against the working poor and the unemployed.

For how does one explain the low-energy, lethargic attitude and approach towards economic diversification? Those who would have largely benefited from the effort have been relegated to an inhumane state of vegetative hopelessness. The cautious narrative line pickers inside the BDP-led government have all the while been sifting through the tomes of economic data and cherry-picking the one that best suits their talking points, forgetting that the data was a cross-section of actual people who lived the reality and knew better.

It would seem Masisi has been dealt a bad hand. But with the lethargic nature with which the BDP government has been approaching economic diversification for two decades, one would be forgiven for thinking that maybe we are living in a poorly scripted Truman Show and that Masisi is afterall part of the ploy. So when the ruling party manifesto from the last general election comes out as a rather vague and unhelpful text, littered with public relations buzzwords, containing no milestones and targets, one does not know if it is a genuine peri-visionary blindness in the BDP or it was his way of getting back at us for thinking we have escaped the loop of economic desperation that has strangled us for decades.

And with the bright minds that the BDP has had at its disposal for the past two decades, both at leadership level and at the rank and file, it is rather baffling and somewhat suspicious how the same efforts at economic diversification have been executed repeatedly all the while expecting different outcomes. Masisi’s manifesto, disappointingly, has the prose and spirit of that insanity. One hopes that Masisi’s transformation team will provide the nation with a possible experiment. Our hope now lies in that project. The transformation team needs to re-think our economic policy.

The Masisi-led BDP promises to “attract FDI by revamping investment and stimulating domestic investment” as a means of job creation. However vague that ‘promises’ maybe, the reality on the ground is much harsher. World Bank data shows a worrying decline in Foreign Direct Investment net inflows from the 2011 peak of just north of one billion dollars to about 230 million dollars in 2018. Compare that with close to three billion dollars invested in Mozambique in 2018 or five and a half billion dollars FDI inflows into South Africa in 2018, countries with whom we compete for FDI.

As a land-locked country, Botswana is, for no fault of her own, at a comparative disadvantage when competing for FDI in sub-Saharan Africa. Again, for no fault of her own, Botswana has a rather small population relative to almost all countries in sub-Saharan Africa. And these metrics matter a lot to foreign investors when they search for a new home for their money. A small population simply means a small market to sell products to and a limiting economic base for ease of business logistics. Lack of access to the sea will prove an extra cost for any foreign investor who settles in Botswana.

When addressing the issue of FDI, the transformation team should consider that for no fault of our own, when competing for FDI, we are starting from a minus. In order to compete pound for pound, we should be outdoing those countries in metrics with which we can compete fairly with them. Most importantly, the team should come up with measures to address our faults. Investment in infrastructure has to be a top priority – this new pattern that was rearing a head where the development budget was undercut by recurrent budgets has to stop. The rumoured impending tax hike is already a mistake that will scare away foreign investors with alternative places they can take their money to.

Promotion and entrenching a spirit of entrepreneurship will go a long way in alleviating the woes of unemployment. Unfortunately, the BDP manifesto does not seem to prioritize this. In the long run, it is our highly viable route out of the current economic bondage, because foreign investors may not come, as they have not in the past decades. Or when they do come, they may leave as they have done in the past. Foreign investors do not owe us their loyalty, and we may only go so far prostituting our souls for them. Masisi’s transformation team has a tall order in front of them that will either usher in a New Botswana or take us back to the dark times we hope to come out of.